Key definitions of Brands applied to the Wine Industry

“A Brand is a mental box”

David A. Aaker, one of the best experts in Branding defines Brand as follows: “A Brand is a mental box”[1]. For him, a Brand is like a box inside the head of someone that represents a consumption experience or a memory left. Note that this definition presupposes at least one consumption experience in order to create any mental value. When applied to the wine industry, this definition raises the question of how some brands or wine appellations can strongly resonate in the minds of some wine lovers (for example, Romanée Conti, Chateau Pétrus, or Chateau Yquem), despite the fact that many of them have never tasted these wines before.

How many have already tasted it? Not so many!

“constituted by the group of speech made about it by the entirety of the subjects involved in its creation”

To answer this question, Andrea Semperini defines the Brand as “being constituted by the group of speech made about it by the entirety of the subjects (individually or collectively) involved in its creation”[2]. Applied to the Wine Industry, this definition makes a lot of sense given that many of the well-known and/or prestigious brands benefit first and foremost from peer-recognition, either by other producers, by professional winemakers, or by oenologists. This definition is not limited to the direct involvement in the wine production process but includes any indirect contribution to the creation of this mental box, such as reviews from wine critics and journalists, sommeliers’ and wine sellers’ recommendations, and peer reviews or wine lovers’ wine crushes. Together, these direct and indirect contributors constitute, without any doubt, the first spreaders and hence the builders of the Brand image. At this point, it has to be noted that this distinction between direct and indirect contributors (in the sense of direct production level involvement versus outsiders to the wine production process) is quite useful in the Wine Industry. Direct contributors may create or be attributed a given brand value based on criteria such as efforts made in the production process, excellence of the practices, reputation of the terroir or the winemakers, but often without ever tasting the wine in question. On the other hand, the indirect contributors add value to the Brand creation process by, almost inevitably, having tasted it first. Otherwise, they can only be considered as simple “word of mouth” spreaders, similar to regular consumers who do not really add value to the mental box creation process.

“a set of physical attributes of a product or service, together with the beliefs and expectations surrounding it”

A less theoretical and more pragmatic definition of the Brand is provided by The Chartered Institute of Marketing which views the Brand “as a set of physical attributes of a product or service, together with the beliefs and expectations surrounding it. It is a one-of-a-kind combination that the product or service’s name or logo should evoke in the minds of the audience.”

The goal of Wine Brands

“main element allowing a wine to move from being easily substitutable in a highly price competitive market”

Almost unanimously, brands seek to move a product (or service) away from being a commodity. Without the notion of brand, wine would just be sold as fermented grape juice, perfectly interchangeable from one to another. As such, according to Economics theory, a Brand helps a given product to escape the fantasized and idealized Pure and Perfect Competition Market also called Atomistic Competition Market (see Léon Walras or Kenneth Arrow).

Therefore, a Brand can be considered as the main element, allowing a wine to move from being easily substitutable in a highly price competitive market to Monopolistic Competition Market as defined by Edward Chamberlain[1]. This enables wineries to charge higher prices even in structurally saturated markets. As a result, we can conclude that developing strong brands is critical to the wine industry’s survival and profitability.

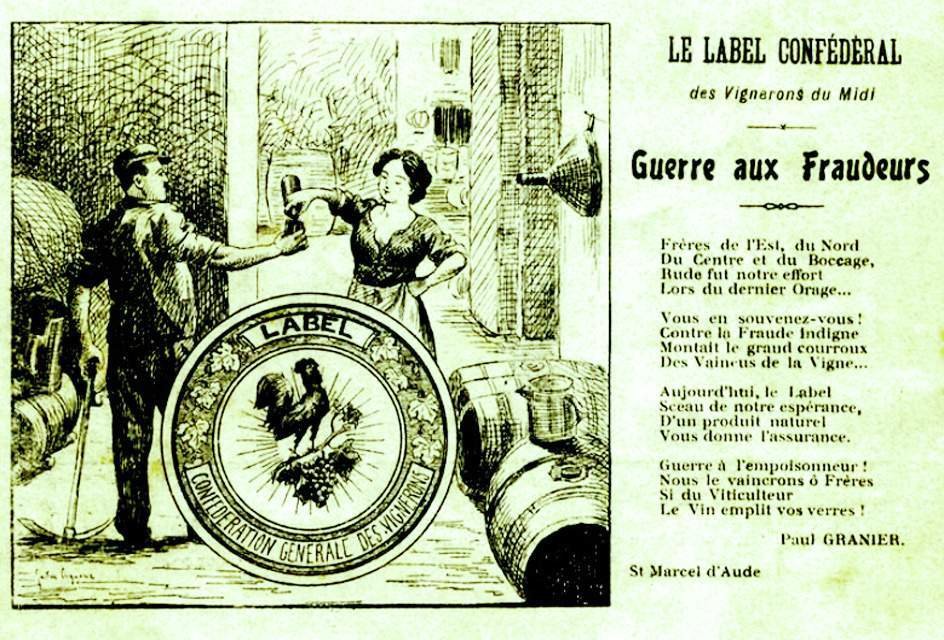

Small wine producers and their respective Brands

Not all winemakers have the financial power to create a powerful and distinctive brand on their own. Most of the time, they do not have sufficient enough financial resources to be allocated to the creation and development of their brand outside of focusing on their production process and doing a few promotional activities throughout the year (events, free samples, competitions, reviews, critics…). Thus, they tend to group with other local similar producers in an effort to promote their wines either to form a larger entity (for example, co-operatives) or through informal trading groups, generic trading bodies, and appellation systems. While the modern European Union appellation system (Protected Denomination of Origin, Protected Geographical Areas…) is borne in France in the early years of the 20th century in an effort to cope with wine fraud and counterfeited products it quickly gained recognition as a powerful Branding vector particularly due to its localized areas of production, peculiar production practices promotion, and the legacy protection shield it offers.

The concept of Soft Brand in the Wine Industry

These diverse European Wine appellations are part of a broader marketing concept called “Soft Brand”, together with the grape varieties (in the US, the grape variety is almost always stated on the label as it has a Brand value for the customer), wine region… While the existence of Soft Brands is disputed by marketing experts, it is a very useful concept to understand the Wine Industry. This concept allows us to analyze whatever signals a consumer uses to decide whether to purchase one product over another. This could be to a nation of origin (such as “Brand Chile”), a location (such as “Bordeaux”), a geographical indicator (such as “Pic Saint-Loup”), a grape type (such as “Cabernet-Sauvignon”), or even a wine style (Fortified wine or Rosé).

To better understand the concept of Soft Brand it is important to pay attention to the Hospitality sector as it is the industry that almost gave birth to this notion. The concept of “Hotel Soft Brand” refers to hotels that belong to a large chain or franchise. Let’s suppose that a large chain wants to buy a great and well-known hotel located in Manhattan. If the name of origin is merely abandoned to the benefit of the chain name, the risk is that regular customers do not want to come anymore to a totally new hotel. As a result, it is crucial that the acquiring chain leave some degree of freedom to the established hotel to preserve its identity and keep its customer base.

“highlights a set of shared features while still allowing the expression of a certain type of uniqueness”

Thus, a Soft Brand can be viewed as a Brand that highlights a set of shared features common to the members of that Soft Brand while still allowing the expression of a certain type of uniqueness and identity within that Brand. In the Wine Industry, Soft Brands can range from grape varieties to countries. However, the best example is probably the European Protected Denomination of Origin (PDO) system. When a customer buys a Pauillac wine they expect a certain type of wine. This type of wine is defined by the AOC Pauillac (also named AOP Pauillac), which comes from a combination of soils, grape varieties, vineyard management requirements, winemaking techniques, aging… But when they buy a wine from Château Lafite Rothschild (a prestigious producer belonging to the Pauillac appellation), they expect a more unique wine than the regular appellation wine. It can come from additional aging, top-notch equipment, excellence in the staff employed…

About the concept of Ladder Brand

“It is a form of hierarchy provided by the producer”

Ladder Brands are designed to provide customers with simple-to-understand “rungs” to support their upgrade to a more expensive and superior brand manifestation. It is a form of hierarchy provided by the producer to facilitate understanding and underline the differences within its portfolio of products. The full spectrum of products belonging to the Ladder Brand benefits from being associated with the most prestigious expression of that brand. In other words, the most prestigious wine of an estate producer carries a mental image so strong in the minds of customers that the other wines it may produce will benefit from it. It is particularly true for the prestigious Chateaux of Bordeaux where their “Seconds Vins” (Second Wines) and “Troisième Vins” (Third Wines) will take advantage of the “Tête de cuvée” reputation and prestige.

There are usually 3 levels in Ladder Brands, namely:

- The Accessible: is the product that is most widely available, least expensive, and likely to be purchased frequently (for example, the Non-Vintage Champagne from Louis Roederer)

- The Stretch: is an affordable option, but only for exceptional occasions (for example, the Vintage Champagne from Louis Roederer)

- The Aspiration: is the most prestigious manifestation of the brand. Despite the fact that the majority of the brand’s customers will never purchase it since it is much more expensive than they are willing or able to spend on wine, it should project its super-premium identity throughout the entire ladder (for example, the Cuvée Christal from Louis Roederer).

Follow me on my Social Media

Wine is a gourmet treasure, do not abuse alcohol!

None of this content has been sponsored

I did not receive any gifts or free samples that could be related to this article

Wine is a gourmet treasure, do not abuse alcohol!

None of this content has been sponsored

I did not receive any gifts or free samples that could be related to this article

REFERENCES

Aaker, David A. Building strong brands. London: Pocket Simon & Schuster, 2010.

Edwards, Corwin D. Review of Review of The Theory of Monopolistic Competition; The Economics of Imperfect Competition, par Edward Chamberlain et Joan Robinson. The American Economic Review 23, no 4 (1933): 683‑85.

Semprini, Andrea. Le Marketing de la marque: approche sémiotique. Paris: Editions Liaisons, 1992.