If you have ever paid attention to any French wine at all, you should have seen many different acronyms on their respective labels. The AOP, AOC, IGP, and VdF are probably the most common. However, they are very controversial nowadays given that many extremely talented winemakers have decided either to leave the AOC or even not to apply for it. This article aims to explore the current French wine appellation system and its flaws while taking a look at recent history to better understand what is happening today.

The current French wine appellation system: a quick reminder

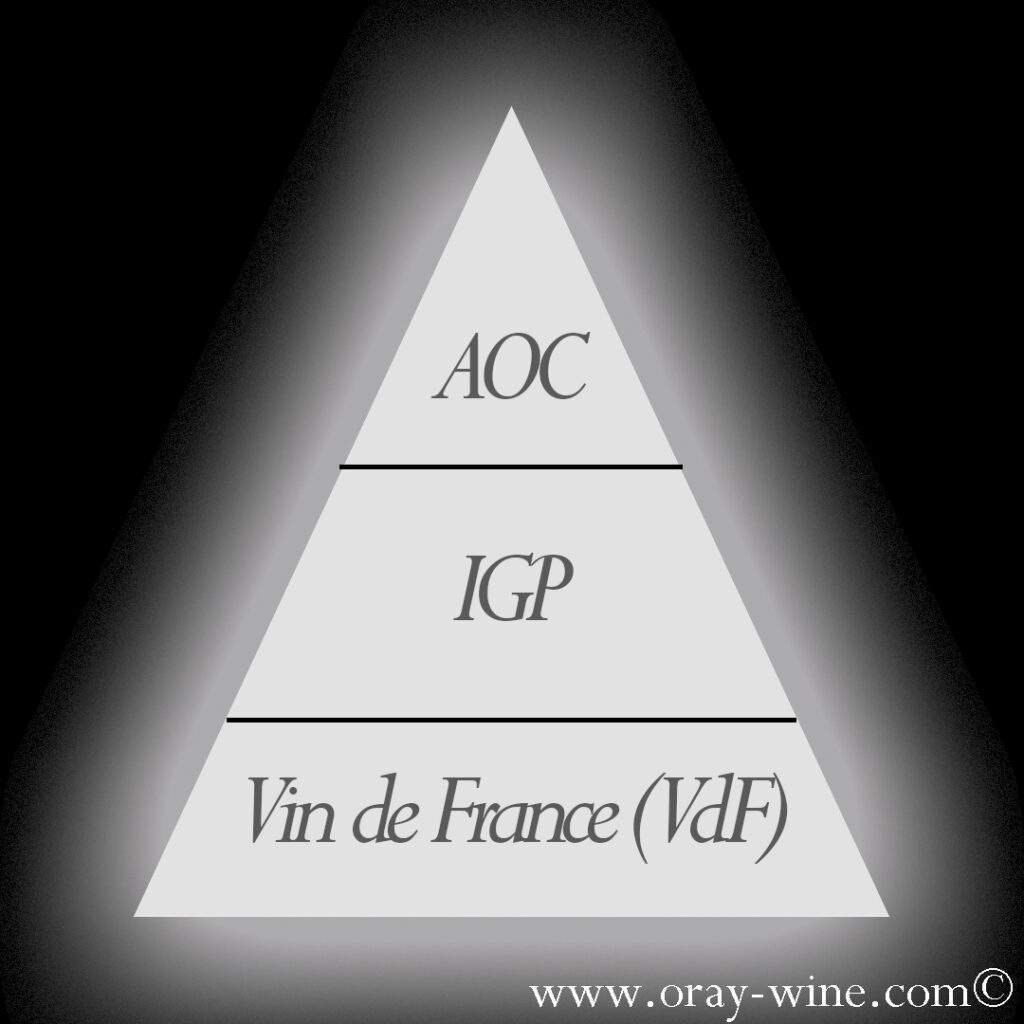

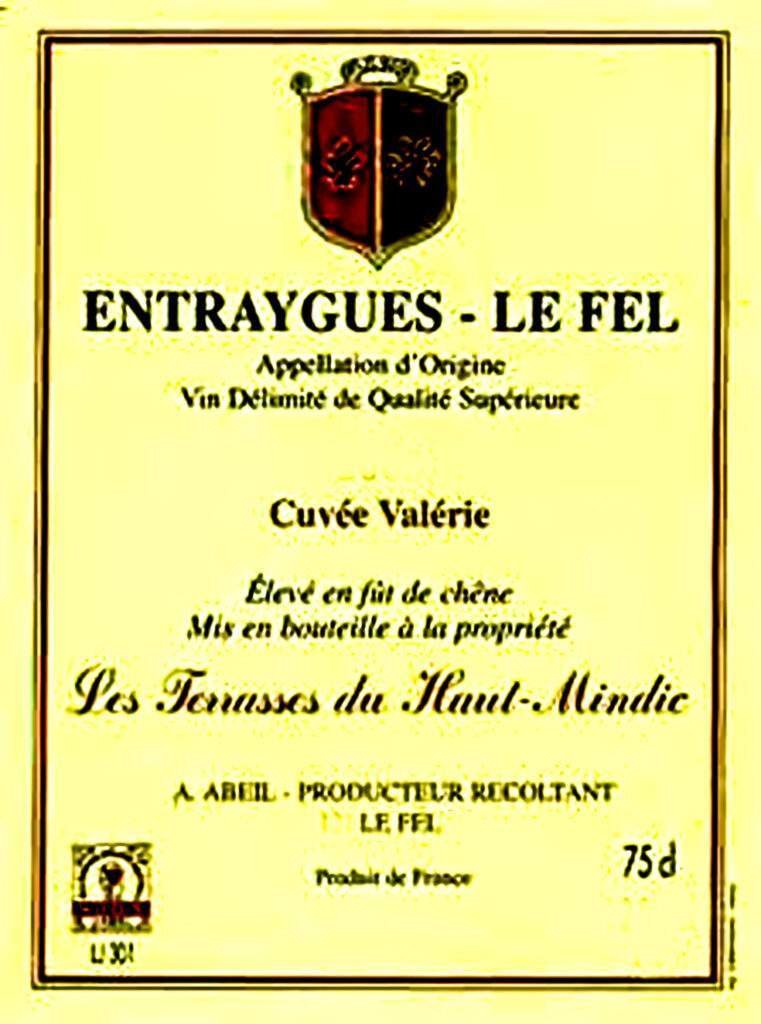

First things first, let’s take a look at today’s most used acronyms and what reality they cover. Schematically speaking, we often represent the French (and European) appellation system as a pyramid where the least demanding constraints seat at the bottom with the VdF (Vins de France = Wines from France), then gradually increase in demandingness through the IGP (Indication Géographique Protégée = PGI = Protected Geographical Indication) to end up with the hardest appellation to obtain, the AOP (Appelation d’Origine Protégée = PDO = Protected Denomination of Origin). Well, that is theoretically true, but theoretically only!

PDO, is it self-sufficient?

That is where things are starting to get more complex, as you may well find extremely high quality wines (sometimes way better than AOP ones) in the PGI (=IGP) category. This is true not only in France, where stunning biodynamic wines by Alexandre Bain do not bear the AOC Pouilly-Fumé designation, but also in Italy, where super-tuscans like Tignanello bear the PGI designation. However, the reasons behind this state of fact are different from one to the other.

“sell their Sassicaia as a DOC while Antinori, for example, has left its Tignanello as an IGT“

For the super-tuscans like Tignanello it is probably more due to the fact that at the time when Tuscans started producing wines from a blend of international grapes like Cabernet-Sauvignon, there was no existing appellation that allowed their use. Then, by default, these wines ended up in the PGI category where rules regarding grapes, winemaking techniques, traditions (etc.) were less stringent. Since then, things have evolved and a new DOC (Denominazione di Origina Controllata = PDO) in Tuscany has been created to cover this gap, the DOC Bolgheri. Consequently, some producers, like Tenuta San Guido, have decided to sell their Sassicaia as a DOC while Antinori, for example, has left its Tignanello as an IGT. That is a prime example of the fact that considering PGI as an inferior wine category is only true on paper. To make things even more complex, the advocates of appellation systems should wonder why Bolgheri is only a DOC and not a DOCG although Super-Tuscans have reached international recognition for decades. (It is important to remember that PDO in Italy is sub-divided into DOC and DOCG, with DOCG representing the most demanding process). But this point is not the main subject of this article, so let’s not get lost in this other controversy.

“wine syndicate in charge of managing the appellation, may league against a winemaker despite the quality of his final product“

For the wines made by Alexandre Bain, whereas I personally find (and I am not the only one) that his biodynamic white wines beat hands down most of the labeled Pouilly-Fumé on the market in terms of quality ; he has not been authorized to sell his wines under the Pouilly-Fumé label. And, the reasons why it happened are worth analyzing. The issue between the producer and the local appellation syndicate has been the subject of many fierce attacks and counterattacks, so let’s not get into too much detail. Let’s just summarize this by saying that it could be considered as an example where some powerful local producers, part of the wine syndicate in charge of managing the appellation, may league against a winemaker despite the quality of his final product. Unfortunately, similar situations have happened in many other appellations and countries (such as Spain and Italy). Aside from the dispute between heavy pesticide users (more focused on mass production and profit-seeking) and passionate biodynamic/organic winemakers (focusing on health and safety for consumers); too many times, blind tasting committees are judged partial and favor the status quo rather than encouraging new paths of quality improvement.

AOC vs. AOP: What is the difference?

I have been asked this question many times, especially by foreigners: “I see AOC or AOP on labels and French people usually call any wine labelled AOP an AOC. I am lost. What is the difference?”. I totally understand that it can be very confusing and that clarification is needed. Simply put, the AOP (Appellation d’Origine Protegée) is the equivalent of the PDO (Protected Denomination of Origin) at a harmonized European level. The AOC (Appellation d’Origine Controllée) can be seen as the inspiration that gave birth to the AOP label. It was a French appellation system designed to distinguish the highest level of quality, mainly for food specialties and wines.

The first wine AOC was created in July 1935 by the INAO (Institut National des Appellations d’Origines) under the proposition of a French Senator. Today, all AOCs in France (wine and non-wine) generate nearly 22.94 billion euros in annual revenue, with alcohol, wine, and spirits accounting for 20.6 billion (source INAO, 2020). After their inception, the different AOCs have rapidly been adopted by the French. They quickly covered many parts of the French gastronomy legacy, such as Noix de Grenoble (1938), Champagne, Poulet de Bresse (1957), Camembert, Roquefort… It really became a symbol of French identity, to such a point that products that are labeled AOP are still called AOC, and that producers keep labelling their products with the AOC mention (instead of AOP, the official European name).

AOC: Where does it come from?

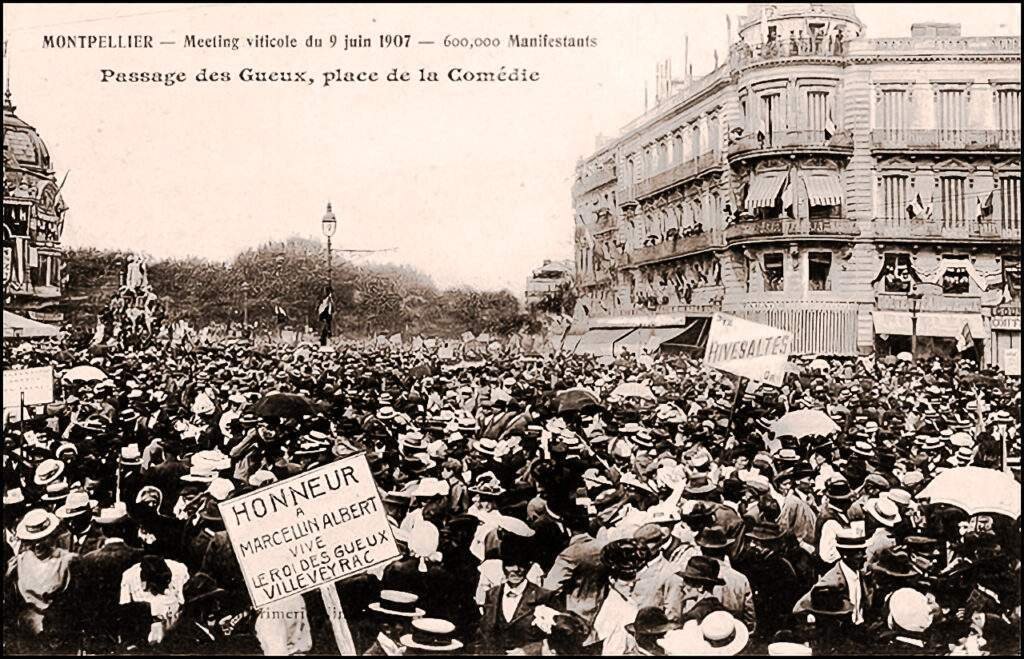

o The first Anti-Fraud Wine law

The creation of the AOC label was a legal answer to fraud and counterfeits that had been waiting for a very long time. Indeed, after the phylloxera crisis in the late 19th century, France became a Far-West in terms of winemaking in order to supply the national demand for wines. Some merchants imported wines from nearly anywhere to blend them, and they sold the same dubious wine under many different labels. To an extreme, it led unscrupulous merchants to transform regular water into wines (sometimes directly on boats) by adding coloring agents and low-quality distilled alcohol (even replacing ethanol with methanol, which made consumers blind).

The two main components of this law were:

- First, “to prevent the watering of wines and the abuse of sugar by a surtax on sugar and the obligation of traders to declare sales of sugar higher than 25 kilograms (55 lb)”; which targeted the practice of making extremely diluted wines that could be chaptalized (adding external sugar and starting fermentation) to increase tremendously the production level

- Second, “No drink may be owned or transported for sale or sold under the name of wine unless it comes exclusively from the alcoholic fermentation of fresh grapes or grape juice”, which targeted the practice of mixing alcohol, coloring agents, and water to produce artificial wines.

o From the Anti-Fraud Wine law to the AOC

After the Anti-Fraud Wine Act was passed, the Fraud and Repression Service was created. Unfortunately, in 1914, World War I began, and the French military authorities needed extreme amounts of wine for the soldiers to keep fighting despite the absolute carnage. The demand was so huge that there was barely enough wine and alcohol for widows and heavily wounded soldiers to lick their wounds.

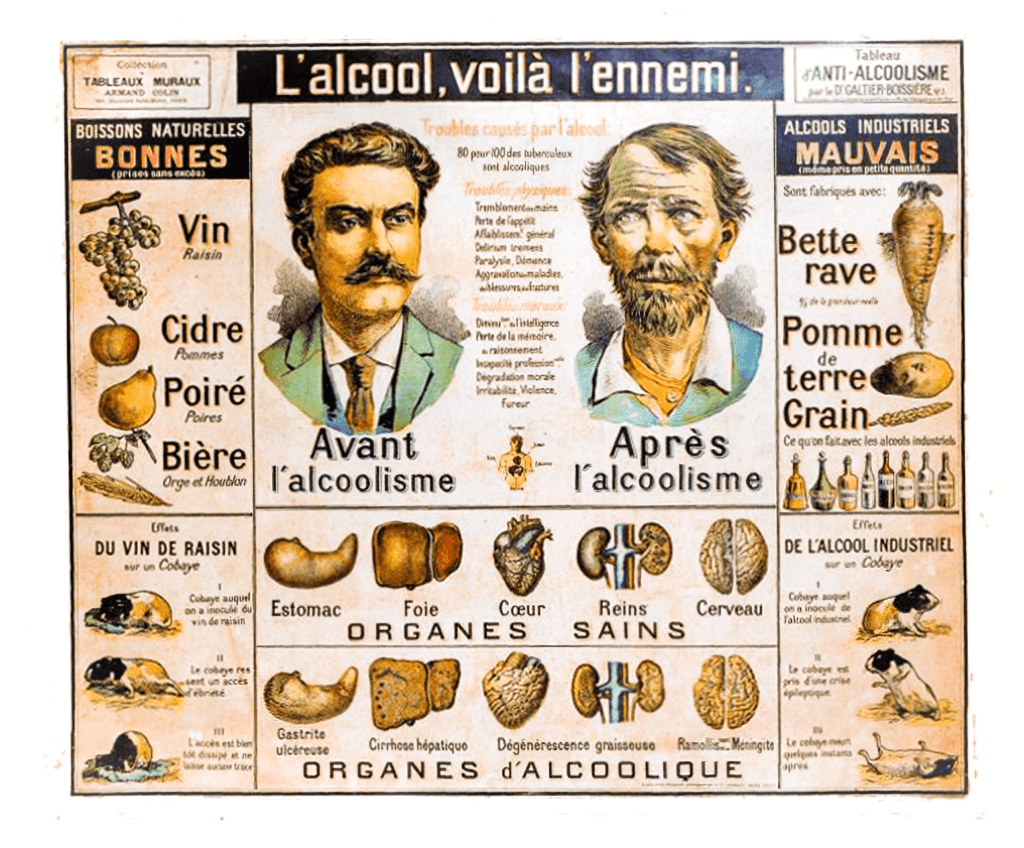

After 1918, the over-consumption of alcohol by soldiers during the war led the remaining part of this generation to be destroyed by alcoholism. This rampant alcoholism, together with the “Années Folles” (the Roaring Twenties), where people just wanted to live and party, did not help to improve the quality of production as the emphasis was put on providing enough alcohol to meet the demand. It was only in 1936 that the INAO (created in 1935) issued its first appellations.

After 1918, Editions Armand CollinPublic Domain Image

o The VdP, AOS, VDQS, and AOC: a brief history

“the risk was for the AOC to be seen as too common and easy to obtain“

Given the success of the first wine AOCs (both in terms of reputation and sales), many other wine-producing regions wanted to have their own AOC. Then, the authorities faced a challenge given that the AOC was supposed to reward excellence and quality; the risk was for the AOC to be seen as too common and easy to obtain (which would have destroyed its value). The VdP (Vin de Pays = County Wines) was created quickly for “table wines” and “cooking wines”, the category for everyday and regular wines with an obligation to be made from grapes and locally. Then, they rapidly established a hierarchy with the creation of the AOS (Appellation d’Origine Simple = Basic Origin Appellation) and the VDQS (Vins Délimités de Qualité Supérieure). VDQS was way harder to obtain than the AOS. VDQS could be seen as an equivalent of the DOC in Italy, with just slightly less stringent rules than the AOC (DOCG in Italy to keep up with the comparison).

Has PGI become the new AOS?

“some PGIs now give their label to wines made from Chardonnay when, traditionally, it has never been grown in the region“

The AOS category disappeared in 1973 in France because most of its members improved their quality enough to switch to the VDQS category. Nonetheless, there is a raging debate because today’s PGIs across Europe are becoming, every year, more and more permissive in terms of grapes, yields, winemaking techniques, etc. They are becoming less and less homogeneous in France and in Europe. Some PGIs are quite restrictive, while others tend to accept almost everything. It has reached a point where some producers and customers are starting to question the true value of labelling their wines as PGIs. And the ‘new world’ trend consisting of labelling bottles by grape variety names does not help. Just to stick to this trend, some PGIs now give their label to wines made from Chardonnay when, traditionally, it has never been grown in the region.

PGI: When the basics are missing?

“made to recognize local, trustworthy, and consistent uses”

Let’s go back to our very interesting French wine appellation system prior to its integration into a harmonized European appellation system. At that time, the distinction between AOS, IGP, and AOC had the same common ground to distinguish them from the VdP (Vin de Pays). According to French law, they were made to recognize “local, trustworthy, and consistent uses” (“usages locaux, loyaux et constants”) to make a given certified final quality product within a certain tradition. Therefore, we can wonder if the PGIs are not moving too fast in accepting certain new grapes and new practices. What is the incentive for producers like Alexandre Bain to label their wines as PGIs? Would it be fair for his wines to bear the same label as certain other producers of the same IGP (who would produce Chardonnay or other grape varieties that we have never seen in the region) when he can to claim AOC Pouilly Fumé?

VDQS: The missing category in today’s European and French winemaking?

The VDQS category was created in 1949 and imposed strict rules regarding winemaking techniques, grapes used, terroir, alcohol level, yields, vine training systems, and vinification. It even required a detailed wine analysis (laboratory) and blind tastings by independent experts. As a result, the VDQS category did not require much time to be adopted by the French customers and gain excellent quality recognition. It really served as a launching pad for many regions before becoming an independent AOC or as an aspiration for the AOS. Sure, the brand power of some super-Tuscans is powerful enough to be self-sufficient. However, some talented but less recognized winemakers are struggling to gain recognition and establish themselves. Wouldn’t it be fair for them to create an in-between category which will recognize distinguishable quality without having to suffer from the flaws of heterogeneous and “one size fits all” PGIs?

Follow me on my Social Media

Wine is a gourmet treasure, do not abuse alcohol!

None of this content has been sponsored

I did not receive any gifts or free samples that could be related to this article

Wine is a gourmet treasure, do not abuse alcohol!

None of this content has been sponsored

I did not receive any gifts or free samples that could be related to this article